The story goes that the legendary violinist, Jascha Heifetz, was stopped on the street by an unsuspecting tourist who asked “how do you get the Carnegie Hall?” The response: “practice, practice, practice.”

This last week, the Charleston Symphony made their concert debut in Carnegie hall. I hope to write more about the experience, but today I wanted to dedicate a post to the question “what is Carnegie Hall?” If you aren’t quite sure about this, you’re in good company. It wasn’t until sometime in college that I learned that the NY Philharmonic moved to a different home nearly 50 years ago, and it wasn’t until much later that I learned the difference between Dale Carnegie and Andrew Carnegie. The steward on our flight was also confused when he enthusiastically yelled over the PA “Anyone on this flight who’s going to Carnegie-Mellon?” We all cheered anyway.

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish-American businessman who made is fortune at the helm of Carnegie Steel, the most extensive iron and steel operations ever owned by an individual in the United States. In 1901 he sold his company to JP Morgan for 300 Million dollars, or the modern equivalent of 11.5 Billion. At that time he surpassed JD Rockefeller as the richest man in the world.

Despite his success, he remained a bachelor until the age of 51 when he married Louise Whitfield. Louise was Andrew Carnegie’s confidant. “I can’t imagine myself without Lou’s guardianship,” he often said. Now this is an important part of the story, because “Lou” was very interested in music. As a member of the Oratorio Society of New York and a good friend of it’s conductor, Walter Damrosch, she introduced her husband to Walter and they began a conversation about a new performance hall for the society. (Happy wife, happy life!)

Plans were submitted in 1889 for a five-story brick and limestone building, containing a 3,000-seat main hall with several smaller rooms for rehearsals, lectures, concerts and exhibits. On the one year anniversary of breaking ground, the hall opened in 1891 for total cost of —get this—$1.25 million. The location of this grand venue was pretty far uptown, 56th st, which was practically in the middle of no where at the time. Today, it all seems quite prescient.

In 1892, shortly after Carnegie Hall opened, they began a long relationship with the New York Philharmonic. This became a pillar of the hall’s existence as concerts were guaranteed to be performed multiple times a week. Carnegie Hall also became a main stop for any big artist traveling in the United States. Everyone from Tchaikovsky, to John Philip Sousa to the Beatles’ American debut happened in this storied building. It became (and remains) the most famous concert hall in America.

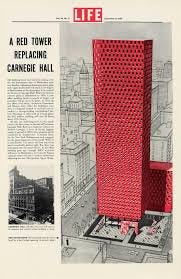

Now, like I mentioned earlier, the New York Philharmonic does not reside at Carnegie anymore (although they do perform there on ocassion). In 1962, the Lincoln Center was built and became the new home for the NY Phil, Metropolitan Opera and NY Ballet (the Juilliard School is also across the street.) When it was announced that the NY Philharmonic would soon be moving farther north, the future of Carnegie Hall looked bleak, how would they continue to fill there hall week after week? In an act of desperation the hall was sold to a developer who intended to tear it down to make way for a very futuristic high rise.

The Carnegie Hall website continues the story. “In December 1959—after making an unprecedented 12 appearances in four days at Carnegie Hall with the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein—legendary violinist Isaac Stern mentioned to philanthropist Jacob Kaplan how sad he was that those performances might have been his last at Carnegie Hall. Stern declared that something more should be done to save the Hall from demolition, and Kaplan agreed to fund a new effort—if Stern would be willing to spearhead the campaign. The violinist happily agreed.”

The city was able to buy back the hall and preserve it as an artistic and historical landmark. Phew! To this day, it remains one of the world’s most famous halls—as an example, our recent performance was on a Wednesday and the next three nights were performances from the Vienna Philharmonic.

It was an honor for us to be able to perform on such a historic stage—and share it with our very on Youth Orchestra and the College of Charleston Orchestra. The audience loved us too—I’m sure it helped that a few hundred Charlestonians made the trip and were in the audience. After the first rehearsal I joked with my bass section “Now that we made it to Carnegie, no more practicing! Thank you Heifetz!”