Every time I get asked a variation of this, I have to bite my tough in order not to say, “I think the question you ought to be asking, my good sir/ma’m, is why would I want to?…” In all seriousness, it’s a decent question and one I’ve tried to tackle a few times. However, I find the answer is so interwoven with technical aspects of the instruments and music theory that when I poke my head up from the weeds I’m met with blank stares and slowly nodding heads. I will do my best to break it down simply and, with any luck, you’ll emerge wide eyed, your head vigorously nodding.

So imagine this: you grew up somewhere in America, perhaps Kansas, and the family car was a minivan. Automatic transmission. You cruise around the burbs, blasting music so loud your speakers shake the neighbors windows, and your friends think your incredibly cool for driving a party bus! There’s a sense of familiarity to the whole experience of driving for you. You grew up in this neighborhood and know your way around these streets, but if, for some reason, you need to go somewhere new, all the road signs are in English and you can easily find your way. You’re comfortable with the size of van; you can parallel park, navigate turns skillfully and carry a big ole’ load of groceries or camping gear in the back.

One morning you awake, and as if you’re still in a bad dream, you find yourself in a very unfamiliar place. First of all you are in the driver’s seat of a European sedan, and the steering wheel is on the right side—by that I mean the wrong side! Also there’s three pedals and a weird pool ball on a stick. MANUAL! You reach for your pocket but it’s empty. You need to find a phone pronto! Somehow you get the car it into first gear, but when you look out the windshield you have no idea what any of the signs mean because you don’t speak German. You pick a direction and head off, but you keep ending up on the wrong side of the street because every time you need to shift gears it requires too much mental concentration to multitask. A series of accidents follows. Ultimately you make it to your final destination, bruised, battered, and with the back bumper dragging on the road behind you. But you made it!

I can see how someone who has never driven a car, perhaps never ridden in a car, or maybe never even seen a car, might witness this comedy of errors and say, “Hey, they made it to their final destination. I guess they know how to drive!” I would have a hard time coming to the same conclusion if that were me in the driver’s seat. So yes, I can technically play the cello, but as I will explain, not well, and not without significant effort, a bit of mental calculus and a lot of mistakes.

The way you play cello and bass—and violin and viola for that matter—is fundamentally the same: 1) create vibrations in the instrument by pulling your bow across part of the string, and 2) change the length of the string to alter the pitch. You change the string length by pinching off the string at different places with your left hand while you do the bow thing with the right. Rather than actually pinching off the string, just pushing it down with different fingers is easier and produces a clearer sound anyway. The shorter you make the string, the higher the pitch goes in much the same way that mice sound high pitched and elephants sound low. Easy enough.

So, here’s where we need to understand a little bit of music theory. Don’t be scared; let’s start with something simple. The notes names go: A,B,C,D,E,F,G and then start over at A again. In between each of those notes are other notes like B flat (Bb) or C sharp (C#). What does this mean for the bass?

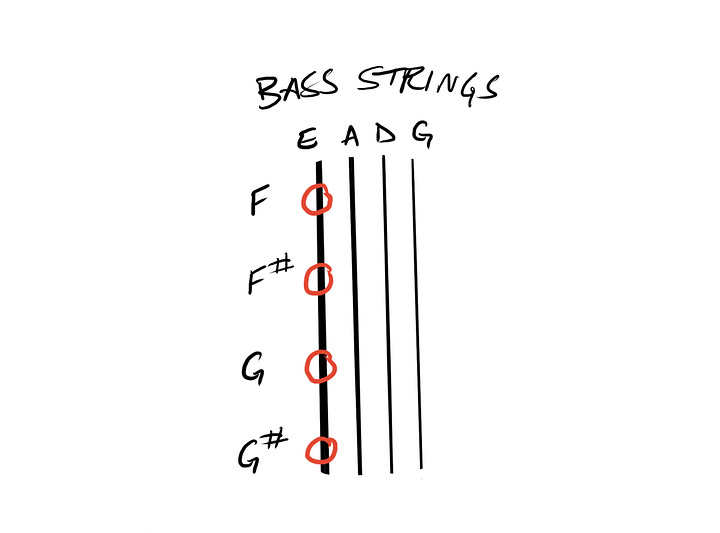

As you can see below, the bottom string on a bass is the note E and the next string over is A. This means that on the first string you can use no fingers (called playing an open string) and play E or push down on the string to play the notes F, F#, G and G# before it’s time switch over the next string (A) and keeping working your way up the scale. I’ve labeled the notes on the first string to make it easy to visualize.

When I’m playing a piece of music, and I see that I’m supposed to play a low F I think, “I know where this is. It’s the first fingered note down there on the E string.” Now, this is where we run into the first complication with switching over to the cello. Their lowest string is a different note entirely: C.

So no longer does playing the first note down on the lowest string make an F, but rather a C#! Since in real life there are no convenient little red circles with note names, to suddenly have to find an F on a cello would require me to have a good minute of finger-counting like a kindergarten mathematician in order to figure out how far up the string I have to go.

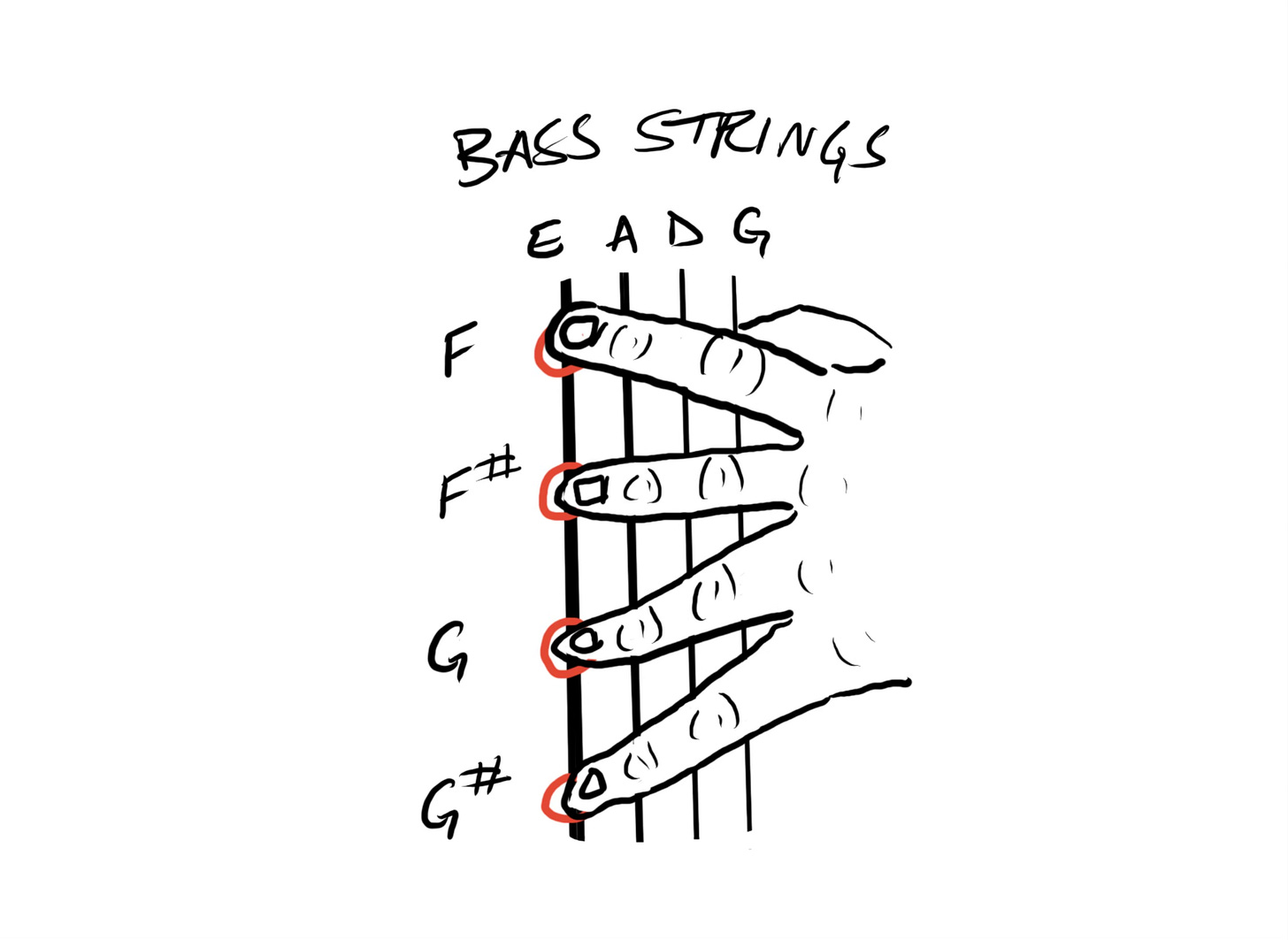

The next complication has to do with the way you actually use your hand to play the notes. Here is an illustration of the bassist’s hand position set up to play the notes F#, G and G#. Gosh those fingers look terrible!

So if you look closely at the drawing you might wonder: “wait, why is the third finger literally doing nothing?” Well, the short answer is that he is doing something, he just doesn’t get his own note (unless that you want to argue that whatever is between G and G# is a note. G# and 1/2?…). Longer answer: a bigger instrument means that everything is bigger and that includes the space to get from one note to the next. Also the strings are thicker and harder to push down especially when you’re going really fast. To spread the fingers wide enough on a bass so that each finger gets its note, and then constantly push down those notes very fast for hours on end will make your hand quite tired and probably result in injury. Not comfortable or practical.

All of this is to explain that in the proper bass hand position, the weakest finger—the pinky—and third finger sorta work together as a team to push down one note while the second and first fingers get their own note. Condensing down to three notes lets the hand not be spread out so wide and makes it easier to push down with the little fingers.

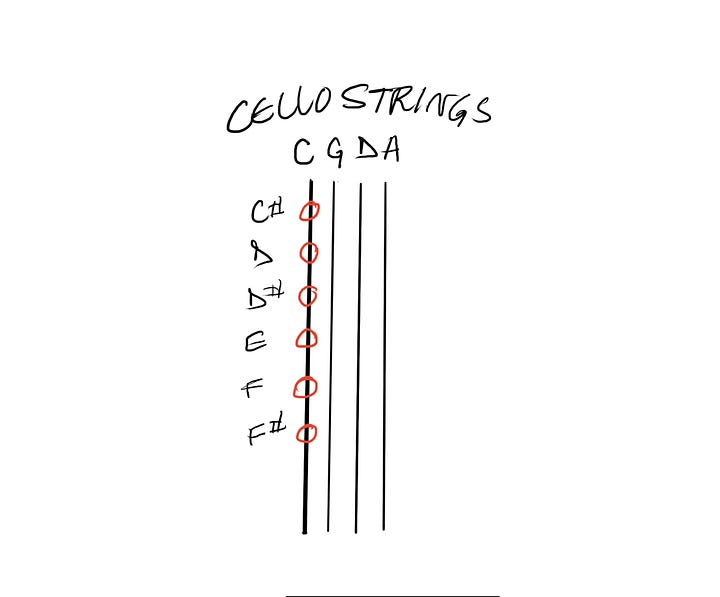

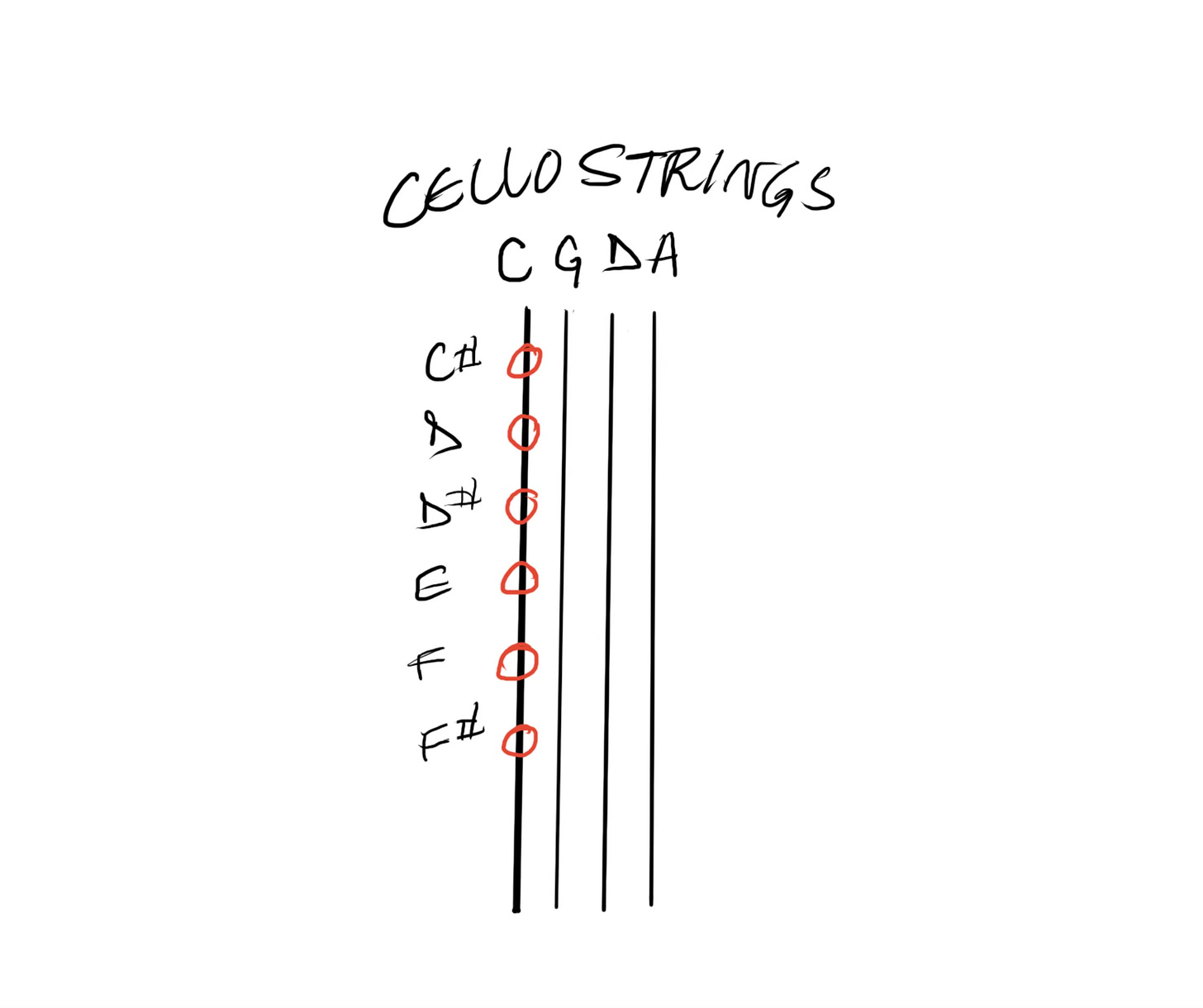

The cello hand position is different. Look how the fingers are used here.

They do give the third finger its own note and they also have a more space between the first two fingers—so much that they can skip over and entire note! This means that, compared to the bass, they are able to fit in a more notes with their hand before needing to move over to the next string. If you look at the side-by-side below you’ll see that the lowest two bass strings are 6 notes apart (E, F, F#, G, G# and A) while the cello is 8 notes apart (C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F# and G.)

So what does that mean for playing the instrument? Well, essentially, if I just tried to put my bass fingers on a cello, it wouldn’t translate very well. Certain neighboring notes might sound right for a second, but the moment I tried playing a few notes in succession or to go up a scale, the exchange would get messed up. The impulse to change strings would not come at the correct time for me. It’s like a slowing clock whose battery is running out and only shows 6 hours for every 8 of real time. The farther along you go, the more out of sync you become.

The last challenge of switching instruments is the mechanical differences. I could get over these, but it’s sorta reminds me of the car analogy again. Imagine your minivan. Every time you push down on the gas and break pedals it feels a bit like stepping on a marshmallow. Then you drive your grandma’s new Porsche convertible and one tap of the gas or break sends your drink splashing all over the windshield. The bass strings are much thicker and it takes a lot more work to get the instrument to make a sound. Cellos (and violins and violas, obviously) need a much lighter touch so you can zip around the instrument more easily. They’re also smaller, so any big shift of the arm to land a high note is going to be a different distance than I’m used to. Of course, these are all learnable with time, but not some special skill I have automatically.

Now a question people don’t often ask is about switching from bass to violin and vice-versa. Maybe it’s because those challenges are a bit more obvious…

> I have to bite my tough in order not to say

I want to hear more about this tough. ;-)

Then you drive your grandma’s new Porsche convertible …..

😂